Tehran, 18 December 2006 (CHN Foreign Desk) -- Studies by a team of archeologists from

Bam Archeological Research Institute led into discovery of a vast city, 42 hectares in area, belonging to the Achaemenid dynastic period (550 BC–330 BC) at the historic site of

Bam, Kerman province. Archeologists assume the city is more likely what referred to in historic texts and

Bisotun inscription as Nashirmeh which was mistakenly taken as the other name for the historic complex of

Pasargadae located in present-day Fars province. Large numbers of potshards dated to the Achaemenid dynastic era were also found by archeologists during their recent studies in Bam’s major fault, situated close to the world famous

Bam Citadel.

Archeologists believe that the discovery of the exact location of Nashirmeh, otherwise referred to as Paishiyauvada, is essential in gaining a greater understanding of the mysterious years of strife and turmoil during the last years of Cambyses’ reign which carried through the years that followed his death.

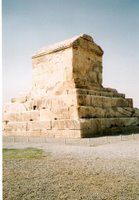

Cambyses II (reigned 529-522 BCE) was the son and successor of

Cyrus the Great, founder of the Achaemenid dynasty, who took over the Persian Empire after the death of his father. There may have been some degree of unrest throughout the Empire at the time of

Cyrus’ death, for Cambyses apparently felt it necessary secretly to kill his brother, Smerdis (Bardiya), in order to protect his rear while leading the campaign against Egypt in 525 BC. He conquered Memphis and the Pharaoh was carried off in captivity to

Susa. Egypt remained as a Persian satrapy for the following 200 years.

While in his Egypt campaign in 522 BC, news reached Cambyses of a revolt back home led by Gaumata the Magian, an impostor claiming to be Smerdis (also known as the false Bardiya

), the youngest son of

Cyrus the Great and Cambyses’ brother. Several provinces of the Persian Empire accepted the new ruler, who bribed his subjects with a remission of taxes for three years. Hastening home to regain control, Cambyses died, possibly by his own hand, more probably from infection following an accidental sword wound. Later,

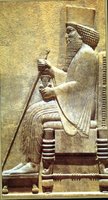

Darius the Great defeated Gaumata and came to power in 521 BC. The new finding could overturn previous conceptions regarding the events that ultimately resulted into transferring of power from the heirs of

Cyrus the Great to the dynasty of

Darius the Great who was from a noble Persian family. It can also shed light on the baffling story of Bardiya’s assassination as some believe he was killed by his brother Cambyses while others say that the person killed by

Darius the Great was the real Bardiya who was murdered due to

Darius’ ambition to gain domination of the Persian Empire. The latter theory is now fading for several reasons raised by the new finding of Nashrimeh outside the boundaries of

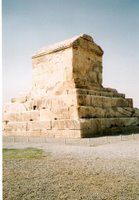

Pasargadae.

One idea that discards the second theory says that if Gaumata was the real Bardiya, why did he refuse to fight

Darius the Great in Pasargadae, the center of Achaemenid power? Moreover,

Darius the Great’s inscription in Bisotun says that the ‘real’ Bardiya was murdered before Cambyses led his campaign to Egypt. Some believe that Bardiya was killed by the order of his own brother, Cambyses, to prevent any possible claim to the throne while Cambyses was off to Egypt.

Yet relatively fewer archeologists and historians hold

Darius the Great responsible for Bardiya’s death and say that Guamata was Cambyses’ brother, Bardiya. These experts argu

e that if Bardiya was killed by Cambyses in 525 BC, there was no way to keep it secret for three years until Guamata claimed the thrown as Bardiya in 522 BC. On the other hand, historians say that

Darius the Great could have easily distorted the reality in his recording in

Bisotun inscription as he does not say much about Guamata except that he was a Magian who rebelled against the Achaemenid king of the time whereas in other historic accounts left from his reign,

Darius the Great clearly states the ancestors, nationality, and residence of his enemies. However, the first idea that says Guamata was an imposter holds more truth based on historic evidence.

“If the Magian Gaumata is Bardiya, son of

Cyrus the Great, why didn’t he stay in

Pasargadae? Why did he initiate his uprising somewhere far from the Achaemenid dynastic capital of

Pasargadae? Therefore, it is much closer to the reality to say that Gaumata was not in fact

Cyrus’ son and for this reason he could not make his way through

Pasargadae,” says Mohammad-Taqi Atayi from the team of archeologists in

Bam.

“If the theories raised by the recent discovery are proved, the political history of early Achaemenid period as we know it today could significantly be challenged … Once the only reliable reasoning which suggests Nashrimeh and

Pasargadae to be one and the same city is disproved, one may conclude the theory that says

Darius rebelled against the Imperial Family is fundamentally flawed and can be questioned,” added Atayi.

According to this archeologist, the names of three cities located in Kerman appear on the inscriptions found in

Persepolis’ ramparts, one of which is Nashirmeh. He also said that that evidence of Achaemenid dynastic period can still be found in Kerman such as potteries discovered in Sassanid era fortresses of Dokhtar and Ardeshir.

One of the strong documents used by archeologists to refute the theory suggesting Nashrimeh and

Pasargadae to be the same is the

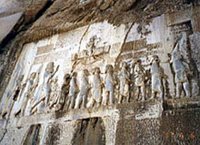

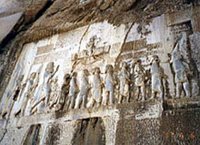

Bisotun inscription. A few years after

Darius the Great rose to the throne, he arranged for the inscription of a long ode of his accession in the face of the usurper Gaumata to be inscribed on a cliff in the Zagros Mountains of Iran that extend to Kermanshah Plain in a historic site known as

Bisotun.

The inscription is carved in both Old-Persian and Elamite languages. The Old-Persian inscription mentions a place called Paishiyauvada while its twin inscription in Elamite has Nashirmeh in place of this word. This shows that Paishiyauvada and Nashirmeh refer to the same place and that Nashirmeh was the Elamite name for Paishiyauvada. On the other hand, since it was not common for a city to have more than one name in one language and since Paishiyauvada and

Pasargadae are both Persian names, it is clear that Paishiyauvada and

Pasargadae are not the same. Therefore, Nashirmeh is not the Elamite equivalent for

Pasargadae and refers to the same city known as Paishiyauvada. Moreover, according to the

Bisotun inscription, Paishiyauvada is the name of a city on the foothills of a mountain called Arakadri, which today archeologists believe is the Jebal-Barez Mountain, south of

Bam in Kerman province. This shows that Nashirmeh was indeed in Kerman.

The rule of the entire Kerman region along with a number of other satrapies was bestowed by

Cyrus the Great to his youngest son, Bardiya. This is why Gaumata chose this region, Paishiyauvada in particular, as the base of his revolt. Moreover, its population of 8000 people was a great advantage. Even if three-quarter of the population were women, children, and the elderly, this still leaves a population of 2000 young men who could make up a powerful army to help Gaumata reach its goal. However, if Gaumata was the real Bardiya, he could have easily made use of all the powers in his hand and unite all the regions under his control to rebel against his brother and seize over

Pasargadae, which evidently never happened, once again proving Gaumata as fraud.

Nonetheless, further studies on the recently discovered Achaemenid city of Nashirmeh (Paishiyauvada) will shed more light on the mysterious years that followed Cambyses’ death.